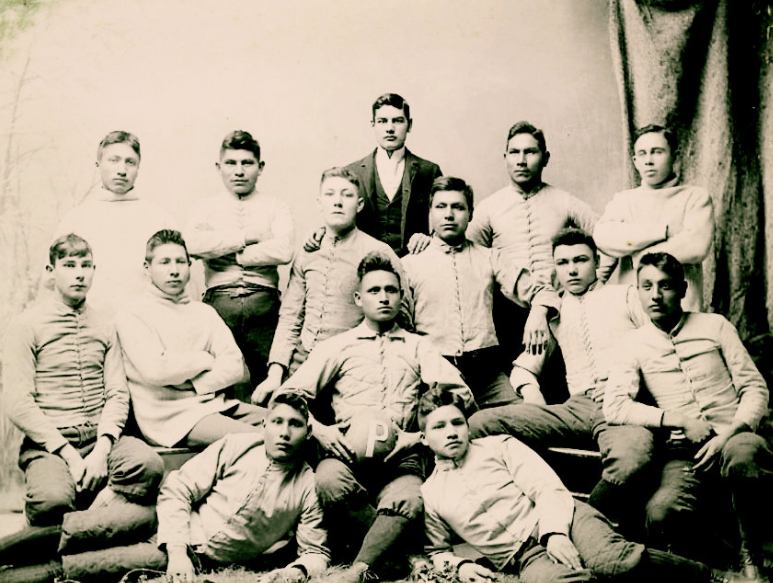

A Native American college football team of 1879

American football game, commonly known as “football” in the United States, officially adopted its name in the 1876 college football season when it shifted from soccer-style to rugby-style rules. Despite the potential for a name change to “rugby,” Harvard chose to retain “football.” In countries where other types of football are prevalent, such as the UK and Australia, it is often called “gridiron” or “American football” to differentiate it. This beloved sport has its roots in the late 19th century, evolving from early rugby and soccer into the strategic, physical game known today.

EARLY HISTORY

The early history of American football traces back to rugby and association football, which evolved from various football games in mid-19th century Britain. Significant rule changes distinguished American football, with Walter Camp, often called the “father of gridiron football,” introducing innovations such as the line of scrimmage and down-and-distance rules.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, college coaches like Amos Alonzo Stagg and Knute Rockne advanced the game, particularly through the forward pass, while bowl games grew in popularity. Professional football began in 1892 when Pudge Heffelfinger signed to play for the Allegheny Athletic Association. The American Professional Football Association was founded in 1920 and became the NFL in 1922, evolving from regional roots to a nationwide phenomenon.

History of American football before 1869

Prehistory of American football

In 1911, influential American football historian Parke H. Davis wrote an early history of the game of football, tracing the sport’s origins to ancient times:

The oldest outdoor game, ball games, can be traced back to 750 BCE, as evidenced by a verse in the Book of Isaiah and a passage in Homer’s Odyssey. The verse states that “He will turn and toss thee like a ball,” suggesting that ball games existed as early as 750 BCE. The passage also mentions that after enjoying a midday meal by the riverbank, they engaged in a game of ball.

Harpastrum is a form of ball game played in the Roman Empire

Football-like games have been played in Europe and beyond since ancient times. These games often involved ball handling and scrummage-style formations. Notable examples include the Greek game Episkyros and the Roman game Harpastum. Over time, various countries developed their own variations, such as New Zealand’s Kī-o-rahi, Australia’s marn grook, Japan’s kemari, China’s cuju, Georgia’s lelo burti, the Scottish Borders’ Jeddart Ba’, Cornwall’s Cornish hurling, Central Italy’s Calcio Fiorentino, South Wales’ cnapan, East Anglia’s Campball, and Ireland’s caid.

There are also references to ball games played in Southern Britain prior to the Norman Conquest, with origins attributed to either southern England or Wales. In the ninth century, Nennius’s *Historia Britonum* recounts a group of boys engaging in ball games (pilae ludus). Additionally, in Northern France, a ball game known as La Soule or Choule, in which the ball was propelled by sticks, feet, and hands, dates back to the 12th century.

Ancient mob football was played between neighboring towns and villages, allowing an unlimited number of players. The objective was to drag an inflated pig’s bladder to designated markers, using various methods to move the ball toward the goal. Sometimes, players would even kick the bladder into a church balcony. The origins of these games can be traced back to England.

Inscriptions from the early 14th century, found at Gloucester Cathedral and the British Museum, depict young men running towards each other with a suspended ball. The images show hands striking the ball, and the final image appears to depict a man with a broken arm, highlighting the dangers of medieval football games. The exact context of these images remains unclear. Many of the earliest references to the sport simply mention “ball play” or “playing at ball,” suggesting that the games of that time did not always involve kicking a ball.

William FitzStephen’s account from 1174 to 1183 describes football activities among London youths during the annual Shrove Tuesday festival. After lunch, students and workers from each school and craft would bring their own balls. Older citizens, fathers, and wealthy men would come on horseback to watch the young players compete, enjoying the excitement of the game and reliving their youth. The emotions stirred as they observed the action and became caught up in the joy of the carefree adolescents.

These antiquated games went into sharp decline in the 19th century when the highway Act 1835 was passed banning the playing of football on public higways. These games still survive in a number of towns notably the Ba game played at Chritmas and Newyear at kirkwall ion the Uppies, Downies and Orkney Islands Scotland, over Easter at Workington in Cumbria and the royal shrovetide Football Match on Ash Wednesday and Shrove Tuesday at Ashbourne in Debyshire, england. Antithetical to social change this anachronism of football continued to be played in some parts of the United Kingdom.

In 1874 Old Division Football being played on the Green at Dartmouth College

In 1586, English explorer John Davis sailed to Greenland to play football with the Inuit people. Later accounts describe an ice-playing game called Aqsaqtuk, where teams lined up parallel to each other to kick the ball through the opposing team’s line and into a goal. In 1610, William Strachey recorded a game played by Native Americans called Pahsaheman. Modern American football has its roots in traditional European games played before American settlement. Early games were similar to “mob football” in England and were mostly unorganized until the 19th century when intramural football games began to be played on college campuses. Princeton University students played “ballown” as early as 1820.

Harvard’s “Bloody Monday” tradition, which began in 1827, involved a massive ballgame between freshmen and sophomores. In 1860, town police and college authorities agreed to stop it, leading to a mock figure called “Football Fightum” being mourned. It took twelve years for football to be played again at Harvard. Dartmouth introduced its own version, “Old Division Football,” in 1871, dating back to the 1830s.

The games in question were primarily “mob”-style, with players attempting to move the ball into a goal area. The simple rules were accompanied by violence and injury. This led to widespread protests and ultimately, Yale, under pressure from New Haven, banned all forms of football in 1860.

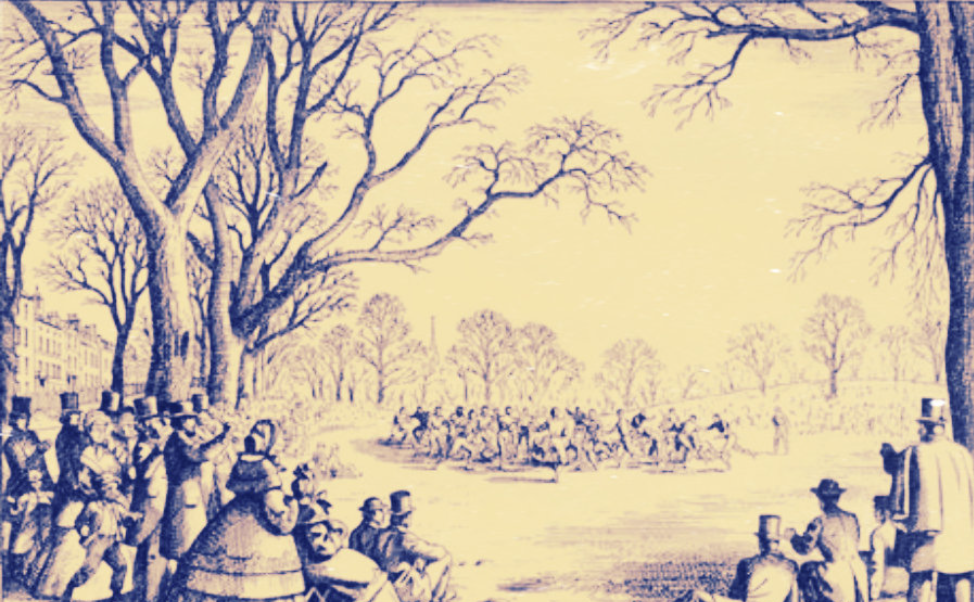

Artistic rendition of an Oneida FC game played at Boston Common

In the 1860s, football gained popularity in East Coast prep schools due to the availability of manufactured inflatable balls, which made kicking and carrying easier. Two main types of football emerged: “kicking” games, which later formed the basis for the rules of the Football Association (soccer) in 1863, and “running” games, which led to the laws of the Rugby Football Union in 1871. A hybrid of these two, known as the “Boston game,” was already being played by the Oneida Football Club, considered the first formal football club in the United States.

By the late 1860s, the game began to make its way back to college campuses, with Yale, Princeton, Rutgers, and Brown universities playing the popular “kicking” game. Princeton adopted rules based on those of the London Football Association in 1867, and in 1868, the Montreal Football Club in Canada began playing a “running” game similar to rugby football.

Early history of intercollegiate football

(1869–1932)

Pioneer period (1869–1875)

The Pioneer Period of American football, from 1869 to 1875, marked the early stages of the sport’s development in the United States, influenced by soccer and rugby, and was played under diverse rules varying between teams and schools.

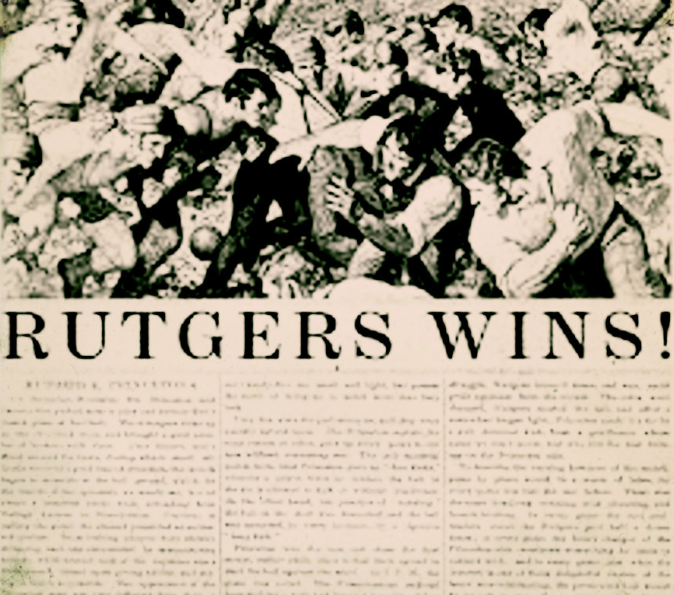

“The Foot-Ball Match”, Nov 1869 Chronicle of the first collegiate game between Rutgers and Princeton at The Targum

On November 6, 1869, Rutgers University played Princeton University (then known as the College of New Jersey) in a game using a round ball and a set of rules proposed by Rutgers captain William J. Leggett. These rules were based on the first set of rules created by the London Football Association, an early attempt by former pupils of England’s public schools to standardize and unify the rules of their school games.

The rules bore little resemblance to the American football game that would later evolve in the following decades. While it wasn’t technically the game we know as American football, it is traditionally considered the first intercollegiate American football game due to the significance of the event. The idea for the intercollegiate game between Princeton and Rutgers was conceived by William S. Gummere, who invented a set of rules and persuaded William J. Leggett to join him.

Rutgers played a game where two teams of 25 players scored by kicking the ball over the opposing team’s goal. Physical contact was common, and Rutgers emerged victorious by a score of 6 to 4. A week later, Princeton played the game under its own rules, with a “free kick” awarded to players who caught the ball on the fly. This rule, later retained in modern American football, was adopted by Columbia in 1870. By 1872, Yale and Stevens Institute of Technology were among the schools that started fielding intercollegiate teams.

Early efforts to organize the game

The third school was Columbia University to field a team. On November 12, 1870, the Lions traveled from New York to Brunswick and were defeated by Rutgers 6 to 3. The team fielded 20 men per side, including two goalkeepers each. The game suffered from disorganization, and the players kicked and battled each other as much as the ball.

In 1870, Princeton and Rutgers played football again, but violence caused a boycott in 1871. In 1872, Columbia faced Yale for the first time, with Yale winning 3–0. Stevens Tech became the fifth school to field a team, losing to Columbia but defeating New York University and City College of New York the following year.

By 1873, college students had made significant strides toward standardizing the game, with teams reduced from 25 to 20 and scoring by batting or kicking the ball through the opposing team’s goal. On October 20, 1873, representatives from Yale, Princeton, and Rutgers met at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City to create the first set of intercollegiate football rules. The rules were influenced more by The Football Association’s rules than the Rugby Football Union’s, and the meeting led to the formation of the first Intercollegiate Football Association.

In 1874 The harvard vs. McGill played

In 1872, Harvard revived its football tradition by allowing players to carry the ball only when the player was being pursued. This led to Harvard refusing to attend rules conferences organized by other schools and continuing to play under its own set of rules. Despite this, the school accepted a challenge to play McGill University from Montreal in a two-game series. McGill played under rugby football rules, allowing players to pick up the ball and run with it at any time. Both tries and goals were counted in scoring, unlike rugby rules of the period, which only allowed a touchdown to be kicked free from the field.

The McGill team traveled to Cambridge to face Harvard, winning the first game under Harvard’s rules 3–0. The following day, they played under McGill’s rugby rules, resulting in a scoreless tie. The games were played with a round ball, marking an important milestone in the development of modern American football. In October 1874, Harvard played McGill again under rugby rules, winning by three tries.

Harvard–Tufts, Harvard–Yale (1875)

Harvard embraced rugby, particularly the use of the try, which was not yet part of American football. In 1875, Harvard played Tufts University in the first game under similar rules, winning. The game involved 11 players, advanced ball by kicking or carrying, and tackles on the ball carrier stopping play. The try later evolved into the modern touchdown.

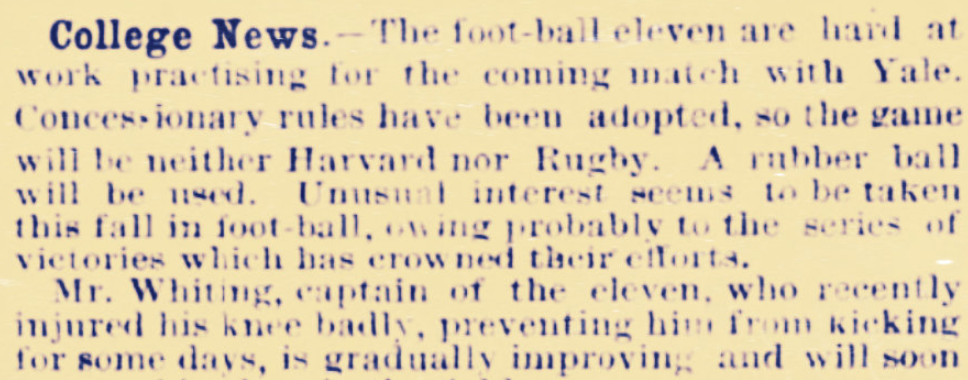

In 1875 News about the Harvard v Yale game played under the “concessionary rules”

Harvard and Yale, inspired by McGill’s football, challenged each other to a game under the “Concessionary Rules,” with Harvard allowing some rugby-style play and Yale allowing soccer-influenced style. They fielded 15 players per team. On November 13, 1875, Harvard won 4–0, marking the beginning of the annual football rivalry, The Game. The game was watched by 2,000 spectators, including Walter Camp, the future “father of American football.” Camp admired Harvard’s style but was motivated to avenge Yale’s defeat. The game was also brought back to Princeton, where it became the most popular version of football.

Period of the American Intercollegiate Football Association

( 1876-1893 )

The years 1876 to 1893 were crucial in the development of American football, highlighted by the establishment and influence of the Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA). During this period, significant strides were made in standardizing the game’s rules, introducing fundamental changes that helped shape the modern version of American football.

In 1876 November 23, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia met at the Massasoit House hotel in Springfield, Massachusetts, to establish standardized rules for American football. The rules were based on the Rugby Football Union’s code from England, introduced to Harvard by McGill University in 1874.

The main difference was the shift from a kicked goal to a touchdown as the primary method of scoring, a change later adopted in rugby. Harvard, Columbia, and Princeton formed the second Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA), marking the first organized effort to regulate the sport. Yale initially refrained from joining due to a dispute over team size, but eventually joined in 1879. The Massasoit Convention of 1876 was a pivotal moment in the early development of American football, marking a transition from soccer-style play and laying the foundation for modern elements.

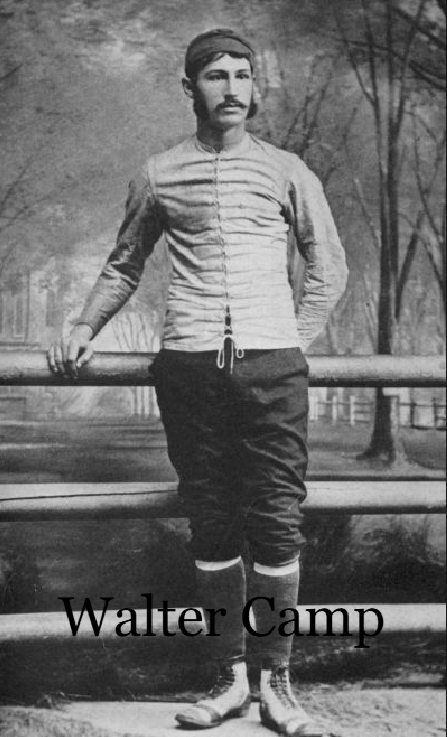

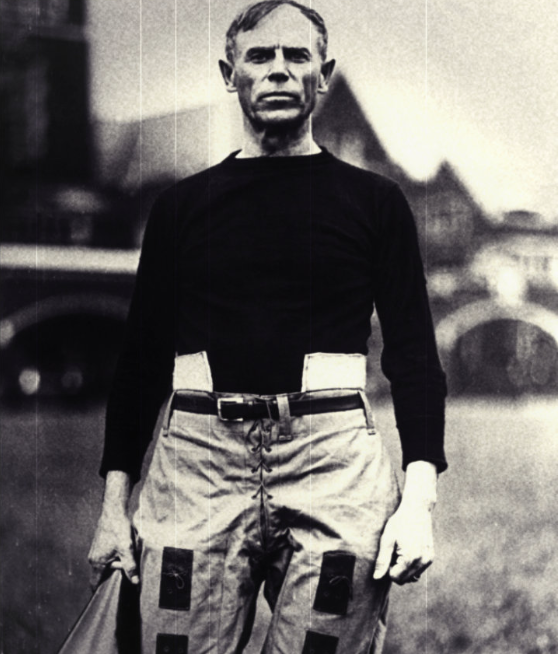

Walter Camp: Father of American football

The Father of American Football Walter Camp captured here in 1878 as the captain of the Yale University football team.

Walter Camp, a prominent figure in American football, excelled in various sports and earned varsity honors at Yale. He participated in Massasoit House conventions, where he proposed a major rule change in 1878, reducing the number of players from fifteen to eleven. This led to a game prioritizing speed over strength.

Camp’s most notable innovation was the line of scrimmage and the snap from center to quarterback in 1880. The snap was initially executed using the center’s foot, but later modifications allowed it to be performed using the hands. Camp’s influence extended beyond American football, as rugby league drew inspiration from his innovations. In 1906, the play-the-ball rule was introduced, closely resembling Camp’s early scrimmage and center-snap rules. In 1966, rugby league adopted a four-tackle rule, modeled on Camp’s original down-and-distance system.

In the 1880 season, teams were limited to 11 players each, a change from previous sizes of 25 players per side from 1869 to 1873, 20 players from 1873 to 1875, and 15 players from 1876 to 1879. Walter Camp introduced scrimmage rules, which significantly changed the game. Princeton manipulated the new system to slow down play, allowing teams to retain possession for extended periods, leading to sluggish matches. To counter this, Camp introduced the down-and-distance rule in 1882, requiring teams to advance the ball at least five yards within three downs to maintain possession. This rule, combined with the line of scrimmage, transformed the game from a rugby variant to a distinct American football sport.

In 1881 Walter Camp significantly influenced American football by implementing significant rule changes. which led to the modernization of the field to 120 by 53⅓ yards. In 1883 camp refined the scoring system, establishing four points for touchdowns, two for safeties, two for kicks and five for field goals, which later influenced rugby union’s adoption of a pointed system in 1890.

In 1887, the game duration was standardized to 45 minutes, with mandatory referees and umpires. In 1888 was legalized in 1888 tackle below the waist was legalized, and officials were equipped whistles and stopwatches in 1889.

Walter Camp, a Yale football player, worked at the New Haven Clock Company until his death in 1925. Despite not being an active player, he remained involved in the sport, attending annual rules meetings and personally selecting an All-American team from 1889 to 1924. The Walter Camp Football Foundation continues this tradition.

One of the most significant changes that ultimately set American football apart was the legalization of interference, or blocking—a move strictly forbidden in rugby-style play. To this day, both rugby codes continue to prohibit interference due to the game’s strict offside rule, which prevents teammates from positioning themselves between the ball carrier and the goal. Early American football players found subtle ways to assist runners, often by pretending to collide with defenders attempting a tackle. Walter Camp first witnessed this strategy in a Harvard-Princeton match he officiated in 1879 and was initially taken aback. However, by 1880, he had fully embraced and implemented blocking as part of his own Yale team’s gameplay.

During the 1880s and 1890s, football teams refined their blocking strategies, introducing complex formations such as the Flying Wedge or “V-trick formation.” Richard Hodge of Princeton first implemented this technique in a match against Penn in 1884. Though Princeton initially shelved the tactic for four years, they reintroduced it in 1888 to challenge Yale’s standout guard, Pudge Heffelfinger.

Heffelfinger countered the V-formation by jumping high into the air with his legs tucked beneath him. Harvard student Lorin F. Deland introduced the flying wedge as a kickoff maneuver in 1892. Harvard effectively used this tactic, trapping the ball and passing it to Charley Brewer within the wedge. However, formations like the flying wedge and “V-trick formation” were banned in 1905 due to safety concerns. The rule change aimed to prevent serious injuries. Non-interlocking interference remains a key element of modern American football, leading to the development of advanced blocking techniques like zone blocking and pass protection.

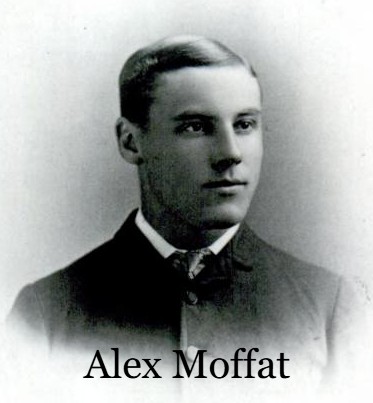

Alex Moffat

A standout in early football, Alex Moffat was considered the sport’s greatest kicker and held a legacy at Princeton akin to Walter Camp’s at Yale. In 1883, football historian David M. Nelson credited Moffat with transforming the kicking game by pioneering the “spiral punt,” calling it “a dramatic change from the traditional end-over-end kicks.” Moffat is also recognized as the inventor of the drop kick.

Alex Moffat, a long-time advisor to Princeton’s football team, played a crucial role in its development. Despite the team’s official absence, a Harvard Crimson report clarified that Moffat ’84 was in charge, with Lea ’96 and Morse ’95 supporting him. After graduation, he continued coaching, officiating, and training at Princeton. Big Bill Edwards, a Princeton player from 1896 to 1899, praised Moffat’s dedication, stating that he was a cheerful, encouraging, and sympathetic coach who dedicated his time to the team’s development.

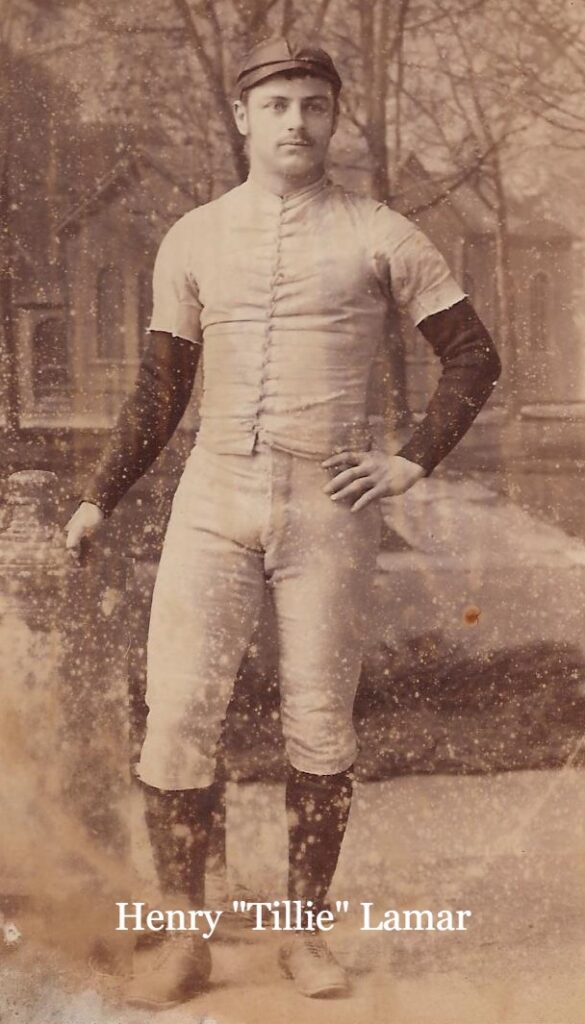

Henry “Tillie” Lamar

In the 1885 football season, a memorable play by Henry “Tillie” Lamar was a 90-yard punt return by Princeton’s Henry “Tillie” Lamar in the closing minutes against Yale. After a controversial Yale-Princeton championship game, the 1885 matchup drew a record crowd and was hosted on a college campus for the first time. The game was a major social occasion, attracting not only students and male spectators but also women. Lamar’s dramatic play significantly boosted the sport’s popularity, and Princeton captain C. M. DeCamp was recognized as the player of the year. The game marked a significant turning point in the 19th century football season.

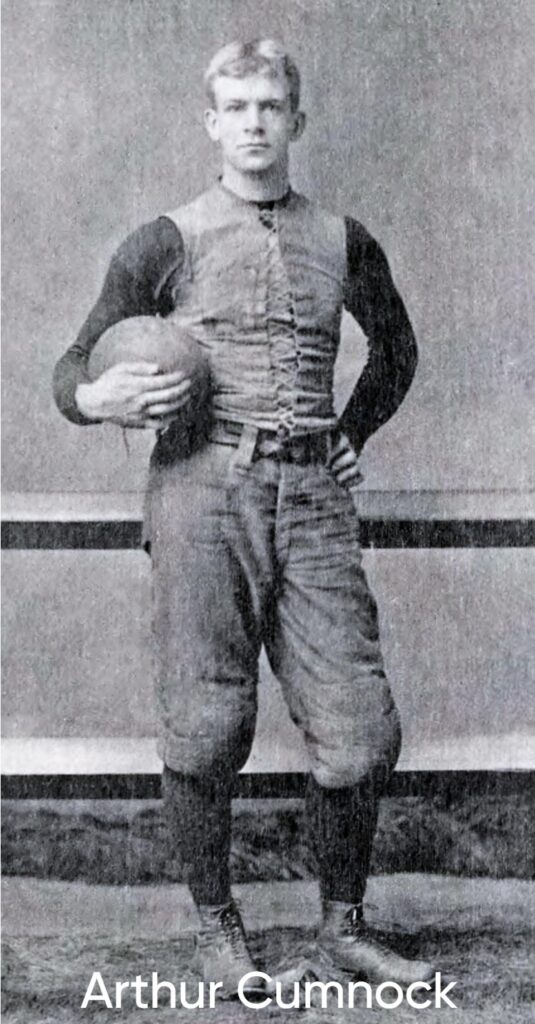

Arthur Cumnock

Arthur Cumnock, a Harvard end, is known for inventing the first nose guard, a protective device that gained popularity. He also played a significant role in spring football practice, leading Harvard’s team in drills on Jarvis Field in 1889. In 1913, Cumnock was named Harvard’s greatest football player. His defensive prowess was praised in an Eastern newspaper for his fearsome tackling in the 1890 Yale game. Cumnock tackled Lee McClung and brought down giant Heffelfinger, demonstrating his exceptional defensive skills. His impact on player safety and spring football practice is significant. Football players can now charge into rough scrimmages without concern due to nose armor, made of fine rubber, which protects both the nose and teeth.

Period of Rules Committees and Conference (1894–1932)

The late 19th century saw a dramatic expansion of college football, with several historic rivalries originating during this time. Among them were Michigan–Notre Dame (1887), Army–Navy (1890), California–Stanford (1892), and Oklahoma–Texas (1900).

November 1890 was a milestone month for the sport. On November 22, Kansas hosted its first collegiate football game as Baker triumphed over Kansas 22–9 in Baldwin City. A few days later, on November 27, Vanderbilt defeated Nashville (Peabody) 40–0 at Athletic Park, marking the first organized football game played in Tennessee. The month concluded with the first-ever Army–Navy Game on November 29, where Navy secured a 24–0 victory.

The roots of college football trace back to the Eastern United States, where Rutgers and Princeton played the first intercollegiate game on November 6, 1869. Harvard, Yale, and Penn were at the forefront of the sport’s evolution, pioneering changes that shaped the game as it is known today.

The formation of the Intercollegiate Football Association in 1876 provided a structured rule set, and influential figures like Walter Camp introduced fundamental concepts like the snap and the downs system. Throughout the early 1900s, powerhouse programs such as Army, Navy, and Cornell dominated the college football landscape.

While football’s power centers have expanded, the East remains a key part of the sport’s legacy. Iconic rivalries and programs such as Penn State, Syracuse, and Boston College continue to contribute to its rich football heritage.

Midwestern college football traces its roots back to the late 1800s, with Michigan, Chicago, and Minnesota leading the way. The first recorded game in the region took place in 1879 when Michigan played Racine College, setting the stage for football’s rapid growth.

The establishment of the Western Conference (now the Big Ten) in 1896 brought organization to the sport, fostering intense rivalries and competitive play. Schools such as Ohio State, Wisconsin, and Illinois quickly rose to prominence, contributing to the region’s football legacy.

By the early 1900s, the Midwest had emerged as a dominant force in college football. Iconic programs like Michigan, Ohio State, and Notre Dame continue to uphold the region’s rich football tradition, influencing the sport on a national scale.

The origins of college football in the South Atlantic date back to the late 19th century, with schools like Virginia, North Carolina, and Clemson playing key roles in shaping the sport. Some of the first documented games in Virginia and the Carolinas helped establish football as a major part of collegiate athletics in the region.

The formation of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association (SIAA) in 1894 provided structure and formalized competition among teams in the South Atlantic states. As the sport gained momentum, schools such as Georgia Tech, Duke, and South Carolina emerged as strong contenders.

By the early 20th century, football in the region had gained widespread recognition, leading to the formation of the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) in 1953. The ACC strengthened the South Atlantic’s reputation as a dominant force in college football, producing some of the sport’s most memorable teams and athletes.

College football began to take hold in the Deep South during the late 19th century, with teams emerging in states such as Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Early matchups featured programs like Auburn, Georgia, and Vanderbilt, laying the foundation for the sport in the region.

The formation of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association (SIAA) in 1894 was instrumental in organizing and regulating football across the South. This conference helped foster competitive rivalries that still thrive today.

By the early 20th century, schools like Alabama, LSU, and Tennessee had begun establishing themselves as football powerhouses. The sport’s rapid growth in popularity eventually led to the creation of the Southeastern Conference (SEC) in 1932, cementing the South’s dominance in college football.

On November 7, 1895, Oklahoma Territory hosted its first college football game, with the ‘Oklahoma City Terrors’ defeating the Oklahoma Sooners 34-0. The earliest recorded game was played on November 29, 1894, with Oklahoma City High School defeating the Terrors 24-0. Coach John A. Harts left for Arctic gold.

Football in the Mountain West region took shape in the early 1900s, led by teams from Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming. Initially, the sport’s expansion was slow due to the region’s geography and smaller school sizes, but growing rivalries helped increase its appeal.

The Skyline Conference, founded in 1938, brought structure to the region’s football programs. This foundation eventually led to the creation of the Mountain West Conference (MWC) in 1999, further solidifying the area’s presence in college football.

Over the years, teams such as Boise State, Air Force, and Fresno State have gained national recognition, with the MWC earning a reputation for producing competitive teams and remarkable upsets.

College football on the Pacific Coast emerged in the late 19th century, with California teams playing some of the earliest organized games. The region’s first recorded game occurred on December 2, 1893, when Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley (Cal) competed in what would later be called the “Big Game.” This rivalry remains one of the longest-running and most celebrated in college football history.

By the early 1900s, the sport had expanded across the West Coast, with programs established at the University of Washington, Oregon, and USC. In 1915, the formation of the Pacific Coast Conference (PCC) helped structure and regulate football in the region. The PCC eventually evolved into the Pac-12 Conference.

Violence and Controversy ( 1905 )

The 1905 college football season became infamous for its extreme violence and lack of safety regulations, resulting in widespread concern. With no standardized protective rules in place, the season saw 18 reported deaths and over 150 severe injuries, triggering public outcry and demands for immediate reform.

President Theodore Roosevelt, a strong advocate for change, met with officials from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton to push for safer gameplay. His efforts contributed to the formation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS) in 1906, which later became the NCAA, bringing much-needed regulation to the sport.

To enhance player safety, several new rules were implemented, including the legalization of the forward pass, the introduction of a neutral zone, and stricter penalties against dangerous tactics. These reforms marked a turning point in football’s evolution, making the game both safer and more structured while preserving its competitive nature.

Move towards modernization and innovation (1906–1932)

Between 1906 and 1932, college football underwent major advancements, moving toward a more structured and strategic style of play. The 1906 rule changes, including the legalization of the forward pass, shifted the game’s focus from sheer physicality to skillful execution. Teams began incorporating innovative formations and play designs that prioritized speed, deception, and technique.

Coaches like Knute Rockne of Notre Dame and Pop Warner of Pitt were instrumental in shaping this new era. Rockne helped popularize the forward pass, showcased in Notre Dame’s 1913 victory over Army, while Warner introduced trick plays and unconventional offensive tactics. Their contributions transformed football into a more dynamic and engaging sport.

During this time, the game’s popularity surged, with larger audiences and growing media coverage. The Rose Bowl, first held in 1902, became an annual event in 1916, helping to establish postseason traditions. The formation of conferences like the Big Ten and the Southern Conference (1921) brought more organization and stability to the sport.

By 1932, college football had solidified itself as a national phenomenon, with refined rules, advanced strategies, and an expanding fan base setting the foundation for its continued growth.

During the early era of the forward pass, the “Big Three” schools remained dominant. Yale’s Ted Coy, recognized for his powerful, high-knee running style, earned a spot as fullback on Walter Camp’s All-Time All-America team.

In 1910, the Minnesota shift, a strategic formation, gained prominence after Yale incorporated it into its playbook. Henry L. Williams, a Yale alumnus coaching at Minnesota, had previously offered to introduce the shift to Yale, but the offer was declined, as the Elis were reluctant to take football advice from a Western program. However, after early setbacks that season, Yale turned to Thomas L. Shevlin, a former player and Minnesota assistant coach, to implement the shift. The adjustment helped Yale secure a 5–3 victory over Princeton and a 0–0 draw against Harvard.

Michigan and Illinois were key forces in the evolution of college football between 1906 and 1932. Under Fielding H. Yost, Michigan refined its high-powered offense and remained a dominant force in the Midwest. Yost’s emphasis on innovation and disciplined play ensured the Wolverines stayed ahead of the competition.

Illinois, led by Robert Zuppke, became a focal point for strategic advancements, with Zuppke pioneering new formations and play designs. The Illini also introduced one of the sport’s most celebrated figures, Red Grange, whose remarkable athleticism and game-changing ability helped propel college football into the national spotlight.

From 1906 to 1932, both Notre Dame and Iowa made lasting contributions to the modernization of college football. Notre Dame, under Knute Rockne, revolutionized the sport by advancing the forward pass, a strategy that gained widespread recognition in their 1913 upset of Army. Quarterback Gus Dorais and Rockne himself, playing as a receiver, demonstrated how the passing game could outmatch traditional defenses. Rockne’s coaching philosophy, focused on agility, misdirection, and precision, helped establish Notre Dame as a football powerhouse.

Iowa, led by coach Howard Jones, brought a different but equally impactful approach, emphasizing tough, disciplined play. The Hawkeyes made history in 1921 by defeating Notre Dame 10–7, breaking the Irish’s long winning streak. This victory underscored the rising competitiveness of Midwestern teams and contributed to the shift of college football’s balance of power beyond the East.

Ohio State became an emerging power in college football between 1906 and 1932. Led by John Wilce, the Buckeyes won their first Big Ten title in 1920, gaining recognition for their structured and tactical style of play.

At the same time, the rivalry with Michigan became more intense, helping shape one of the most legendary clashes in the sport. The Buckeyes’ steady success positioned them as a future force in college football.

Between 1906 and 1932, Vanderbilt played a pivotal role in advancing football in the South. Under the leadership of Dan McGugin, the Commodores established themselves as a powerhouse, winning numerous Southern titles and proving that Southern teams could compete at a high level.

McGugin’s strategic approach and Vanderbilt’s disciplined style of play helped set a new standard for football in the region. The team’s sustained success contributed to the rise of Southern football and helped pave the way for the formation of the SEC, solidifying the South’s presence in the sport.

During the period from 1906 to 1932, Georgia Tech rose to prominence in Southern football. Guided by visionary coaches John Heisman and William Alexander, the Yellow Jackets gained recognition for their tactical creativity and high-powered offensive play. Heisman’s innovative coaching methods reshaped the game, giving Tech a distinct advantage over its competition.

A defining moment in the program’s history came in 1916 when Georgia Tech secured a historic 222–0 victory over Cumberland, demonstrating their supremacy on the field. The Yellow Jackets’ success not only solidified their place in football history but also played a crucial role in enhancing the status of Southern teams in the sport.

From 1906 to 1932, Centre College made an enduring impact on college football by surpassing expectations. Under coach Charlie Moran, the small Kentucky program gained a reputation for taking down powerhouse teams, demonstrating that Southern football could rival the dominant Eastern programs. The defining moment came in 1921 when Centre stunned Harvard with a monumental 6–0 victory, widely regarded as one of the sport’s greatest upsets.

Led by star player Bo McMillin, Centre’s team exhibited skill and resilience, helping to elevate the perception of Southern football. Their success not only earned national attention but also played a role in shaping the future of the sport.

Often referred to as the “Game That Changed the South,” the 1926 Rose Bowl was a turning point in college football history. Alabama’s narrow 20–19 win over Washington proved that Southern teams could compete at the highest level, defying long-held perceptions of regional inferiority.

Guided by coach Wallace Wade, Alabama’s triumph earned national respect for Southern football and paved the way for future success. This victory not only elevated Alabama’s status but also marked the beginning of the South’s rise as a dominant force in the sport.

The Pacific Coast significantly influenced the modernization of college football from 1906 to 1932. The introduction of the forward pass in 1906 prompted teams like Stanford, USC, and California to develop more advanced offensive strategies, which transformed the style of play.

The establishment of the Pacific Coast Conference (PCC) in 1915 organized competition in the region, allowing teams to improve and compete at a higher level. Under Coach Howard Jones, USC gained prominence by winning the 1932 Rose Bowl against Tulane, demonstrating the strength of West Coast football.

Coaches like Pop Warner at Stanford introduced innovative tactics to the game, while USC’s growing national recognition shifted perceptions of the region’s football capabilities. By the early 1930s, Pacific Coast teams had firmly established themselves as strong competitors in the evolving landscape of college football.

From 1906 to 1932, as college football evolved, Stanford became a dominant force, particularly after Pop Warner took over as head coach in 1924. Warner introduced groundbreaking offensive strategies, including the double-wing formation, which shaped future football tactics.

Stanford showcased its strength with three straight Rose Bowl appearances between 1927 and 1930. The 1926 Rose Bowl, which ended in a 7–7 draw against Alabama, played a crucial role in raising the national profile of West Coast football.

With Warner’s innovative coaching and Stanford’s competitive success, the program emerged as a powerhouse, reinforcing the Pacific Coast’s prominence in the sport.

Innovators and Motivators

(1894–1932)

Although Walter Camp is commonly regarded as the “Father of American football,” the game’s development was a joint endeavor, with numerous people playing a role in its early progress.

Parke H. Davis

Born in 1872, Parke H. Davis was an influential figure in the history of American college football, best known for his work as a historian, writer, and statistician. He was a pioneer in compiling comprehensive records and statistics for the sport, helping to organize and preserve the history of college football.

Davis is often credited with being one of the first to create an official list of All-America teams, which became a key method for evaluating the best players each season. His efforts in documenting games, coaches, and players played a vital role in shaping college football’s identity as a national pastime. While Davis did not play or coach at a high level, his contributions as a historian and statistical analyst were essential to the sport’s growth and popularity.

Amos Alonzo Stagg

Serving as the head coach at the University of Chicago from 1892 to 1932, Amos Alonzo Stagg built a powerhouse football program that became one of the nation’s top teams. His time at Chicago is marked by not only his success on the field but also his numerous contributions to the game. Stagg helped popularize the forward pass, created the huddle, and introduced the “triple-threat” position. He also made key innovations like using a smaller, lighter football and developing new blocking techniques.

Throughout his coaching career, Stagg led the University of Chicago to several Big Ten championships, including a perfect season in 1905. His disciplined and innovative coaching approach earned him legendary status in the sport. Stagg played a crucial role in the creation of the Big Ten Conference and in the broader growth of college football. His legacy continues through his influence on future generations of players and coaches. Stagg was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame, cementing his place as one of the most iconic figures in football history.

John Heisman

Born in 1869, John Heisman was a pioneering figure in early college football. A coach and innovator, he coached at Auburn, Georgia Tech, and Rice, leaving a lasting legacy on the game. Heisman introduced the huddle and promoted the forward pass as a key offensive weapon, helping transform football into the dynamic sport it is today.

His emphasis on speed and agility over brute strength was groundbreaking. At Georgia Tech, his teams enjoyed remarkable success, including a 222–0 victory over Cumberland in 1916, the largest margin of victory in college football history, and a national championship in 1917. Heisman was also instrumental in shaping the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association (SIAA) and influencing national football rules. His legacy lives on through the Heisman Trophy, awarded annually to the top college player. John Heisman passed away in 1936, but his contributions to the sport continue to be felt.

William H. Lewis

Born in 1882 in New York, William H. Lewis was a trailblazing figure in college football and American sports history, known for his groundbreaking contributions during the early 20th century. A standout player at Harvard University, Lewis played for the Crimson football team from 1904 to 1907, excelling as a fullback and tackle. His athleticism and skill helped propel Harvard’s football program to prominence within the Ivy League.

As one of the first African Americans to compete at such a high level in college football, Lewis played a crucial role in breaking racial barriers, challenging stereotypes, and paving the way for future African American athletes in the sport. Following his football career, Lewis became a distinguished lawyer, politician, and community leader. He made history as the first African American Assistant Attorney General in Massachusetts and was a strong advocate for civil rights.

Lewis’s induction into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1912 was a significant milestone in his career and legacy. His influence extended well beyond the football field, as his contributions in various fields and his role in the civil rights movement established him as an important figure in American history.

Fielding “Hurry Up” Yost

Fielding “Hurry Up” Yost, born in 1871, was one of college football’s most influential coaches, famous for his innovative strategies and leadership skills. He is particularly credited with developing the “hurry-up” offense, a fast-paced, no-huddle approach that kept opposing defenses unsettled and unable to make substitutions. Yost’s coaching career reached its peak in 1901 when he became the head coach of the University of Michigan football team. Under his guidance, Michigan rose to prominence as a football powerhouse, achieving a remarkable record and multiple championships, including an undefeated season in 1901.

The “hurry-up” offense revolutionized the game by keeping the pressure on defenses and preventing them from establishing a rhythm. Beyond his coaching success, Yost also contributed to the establishment of the Big Ten Conference and played a vital role in organizing college football at a regional level. His legacy as a coach and innovator continues to shape the game today, as his strategies and influence helped define the future of college football.

Eddie Cochems

Eddie Cochems was an early pioneer in college football, best known for his innovative use of the forward pass. As the head coach at St. Louis University, Cochems is credited with being one of the first to effectively incorporate the forward pass into the game, a strategy that would eventually revolutionize football.

His major contribution came in 1906, when the forward pass was legalized. While many teams were hesitant to adopt this new strategy, Cochems eagerly embraced it, particularly in a game against the University of Chicago. In that game, his quarterback, Paul Cochems (his brother), threw successful passes, proving the forward pass could be a potent offensive weapon. Cochems’ early use of the forward pass helped reshape football and set the stage for future coaches to integrate passing plays into their offensive schemes. Though his coaching career was relatively brief, Eddie Cochems’ impact on the sport remains significant, as his innovative approach helped establish the pass as a central element of modern football’s high-scoring offenses.

Henry L. Williams

Henry L. Williams was a significant figure in the early development of college football, particularly renowned for his coaching at the University of Minnesota. Between 1900 and the 1920s, Williams made vital contributions to the sport. His most notable achievement was popularizing the “Minnesota Shift,” an innovative offensive formation that revolutionized football. The Minnesota Shift involved a moving offensive line, which added unpredictability and strategic depth to the game.

The formation was adopted by other teams, including Yale, and became widely recognized. It marked a departure from traditional, static blocking techniques, allowing for more dynamic and deceptive plays. Williams was also an accomplished coach at Minnesota, where he helped elevate the team to prominence by securing several Western Conference titles. His focus on strategy, discipline, and innovation helped cement his reputation as a leader in football. Known for his ability to develop and motivate players, Williams is considered one of the early pioneers of modern football coaching, and his influence on the game is still felt through the Minnesota Shift and his success at Minnesota.

Glenn “Pop” Warner

Born in 1871, Glenn “Pop” Warner was one of the most influential coaches in college football history, known for his pioneering innovations and a highly successful career at several universities, particularly Stanford University and the University of Pittsburgh. Considered one of the greatest football minds ever, Warner’s legacy extends far beyond the college ranks. He was instrumental in shaping youth football, believing in the importance of teaching the game’s fundamentals from a young age, which helped pave the way for future athletes. Warner’s influence also reached the professional game, where his coaching methods and strategies earned him recognition and respect from both college and NFL coaches.

Robert Zuppke

Robert Zuppke was a pioneering coach in American football, best remembered for his successful tenure at the University of Illinois from 1913 to 1941. Over the course of his nearly three-decade career, Zuppke compiled a record of 131–81–12, leading the Illinois Fighting Illini to six Big Ten championships (1914, 1915, 1923, 1927, 1928, 1931).

A true innovator, Zuppke contributed to the development of the single-wing offense and incorporated tactical formations centered around deception and misdirection, strategies that shaped future coaching philosophies. His coaching approach, which prioritized discipline and readiness, was key to his teams’ success. Illinois under Zuppke produced legendary players, including the iconic Red Grange. Zuppke’s teams also appeared in major bowl games, such as the 1923 Rose Bowl, and his enduring legacy shaped both the Illinois program and the broader college football landscape. Even after retiring, he remained an influential figure in the football world.

Dan McGugin

Dan McGugin was a distinguished American football coach, celebrated for his impactful tenure as head coach at Vanderbilt University from 1904 to 1917 and again from 1919 to 1934. Known for his ability to build a strong and competitive program, McGugin remains one of the most significant figures in Vanderbilt’s football history. With an impressive coaching record of 197 wins, 55 losses, and 19 ties, he became one of the most successful coaches of his era.

McGugin led Vanderbilt to four championships in the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association (SIAA), establishing the team as a formidable contender in early 20th-century college football. His teams were recognized for their discipline, toughness, and strategic innovations.

He played a crucial role in the creation of the Southern Conference, which later evolved into the Southeastern Conference. His coaching produced talented players who excelled in both college football and professional leagues. McGugin’s success was driven by his skill in recruiting and developing players who could compete with top national programs. His coaching philosophy emphasized both mental and physical preparation, teamwork, and rigorous practice routines, all of which contributed significantly to his teams’ success.

Even after his coaching career, McGugin remained an influential figure at Vanderbilt, and his legacy continues to be honored for the profound impact he had on the university’s football program.

Gil Dobie

Gil Dobie was a renowned football coach at the University of Washington from 1908 to 1916, where he achieved an undefeated record of 58–0–3. He led Washington to multiple Pacific Coast Conference championships and was key in popularizing the T-formation, a strategy that influenced modern football. Dobie’s disciplined teams made Washington a powerhouse, and his legacy continued with a successful stint at the University of Minnesota. He remains remembered for his undefeated seasons and significant impact on college football.

Dana X. Bible

Dana X. Bible was a respected American football coach and athletic administrator, best known for his successful tenure at the University of Texas. Serving as head coach from 1937 to 1946, he led the Longhorns to a 58–31–3 record, winning multiple Southwest Conference championships and a Cotton Bowl victory in 1943. Bible was an innovator, refining the T-formation offense, which became widely adopted in college football. Before Texas, he revitalized the Nebraska Cornhuskers, leading them to several conference titles. As Texas’ athletic director, he helped shape the future of college athletics. Bible’s legacy is marked by his influence on the game and his leadership in building successful programs.

Andy Smith

Andy Smith is celebrated as one of the most successful and innovative coaches in college football history, primarily for his role at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1921 to 1932. During his tenure, Smith led the Golden Bears to five Pacific Coast Conference championships and a national title in 1920. His impressive coaching record of 74–19–5 reflected the dominance of his teams.

Smith was instrumental in shaping college football on the West Coast, implementing a balanced offensive strategy and disciplined defense. He played a crucial part in popularizing the T-formation offense, a key innovation of the era. Smith’s ability to mentor players who later thrived professionally further solidified his influence, leaving a lasting legacy at Cal and within the sport.

Howard Jones

Howard Jones was a legendary football coach at the University of Southern California (USC), where his innovative coaching methods and success on the field made him a key figure in college football history. Born in 1886, Jones began coaching at USC in 1925 and spent 15 years building the Trojans into a powerhouse, with a stellar record of 121–36–13. His teams won four Pacific Coast Conference titles and achieved national recognition, with the 1932 USC team winning the Rose Bowl and being named national champions.

Jones was a pioneer in offensive strategies, introducing the single-wing formation and creating balanced, disciplined teams that excelled at both offense and defense. His emphasis on toughness and preparation played a vital role in USC’s rise to prominence in the college football world.

Knute Rockne

Knute Rockne regarded as one of the greatest figures in American football, Knute Rockne was born in 1888 in Voss, Norway, and went on to become a coaching legend, most notably at the University of Notre Dame. He took over as head coach in 1918 and, over the course of 13 seasons, built Notre Dame into a football dynasty, compiling an extraordinary 105–12–5 record and winning three national championships (1924, 1929, 1930).

Rockne’s innovations were key to shaping the modern game of football, including his development of the forward pass, which became a major component of offensive strategy. He also popularized the Notre Dame Box, an offensive formation that became a signature of his teams’ tactics, and his overall impact helped modernize the sport.

Early history of professional football

( 1892-1932 )

From 1892 to 1932, professional American football underwent key developments that were instrumental in shaping the future of the sport and paving the way for the creation of the National Football League (NFL).

Early players, teams, and leagues (1892–1919)

From 1892 to 1919, professional American football took shape, with the rise of early players, teams, and leagues that formed the foundation of the game we know today.

During this period, the first professional football clubs were established in cities across the country, and players began to receive pay for their participation. Teams such as the Canton Bulldogs, Decatur Staleys, and Chicago Bears played significant roles in the sport’s growth.

These early foundations led to the creation of leagues like the American Professional Football Association (APFA) in 1920, which would later evolve into the NFL. Despite facing challenges in organization and finances, these early teams and leagues set the stage for the future of professional football.

Early years of the NFL (1920–1932)

The period from 1920 to 1932 was pivotal in shaping the NFL. The league was founded in 1920 as the American Professional Football Association (APFA) before officially adopting the name National Football League in 1922.

This era was characterized by growing pains, including financial difficulties and organizational struggles. However, teams like the Chicago Bears, Green Bay Packers, and New York Giants emerged as influential forces in the league’s growth. The NFL gradually started to gain traction as a serious alternative to the long-established dominance of college football.

By 1932, the NFL had begun to form a more structured system, with the introduction of playoffs and a championship game. The iconic 1932 championship game, played in a heavy snowstorm, proved to be a turning point in showcasing the league’s future potential.

During the NFL’s formative years (1920–1932), a few key teams helped establish the league and contributed significantly to its growth. These teams were vital to the NFL’s early success and played a pivotal role in the league’s development into the powerhouse it is today.

The early teams were crucial in establishing the NFL’s foundation, helping it grow into the professional football powerhouse it is today. Teams like the Akron Pros, Canton Bulldogs, and Chicago Bears were essential in the formation of the league, opening the door for future expansion and achievements. These franchises were pivotal in transforming the NFL from a small, regional organization into a national, organized, and competitive sport.

The 1932 NFL Playoff Game was a groundbreaking event, marking the first-ever playoff game in NFL history. It was played on December 18, 1932, between the Chicago Bears and the Portsmouth Spartans (later known as the Detroit Lions), after both teams ended the regular season tied for first place.

Taking place at Stagg Field, University of Chicago, this game was significant for introducing the NFL’s playoff system, which was a departure from the previous method of determining the league’s champion solely based on regular-season standings. The Bears won 9-0, claiming their first NFL championship. This victory also marked the start of the NFL’s postseason, which would become a fundamental part of the league’s future growth.

The 1932 playoff game was key in shaping the NFL playoff structure, laying the groundwork for the modern postseason format we see today.

Early history of youth and high school football ( 1863-1932 )

From 1863 to 1932, the early development of youth and high school football marked a transition from informal, localized games to a more structured and competitive sport. The Oneida Football Club in Boston, founded in 1863, was the first organized team in the United States, playing a form of football that combined elements of association football (soccer) and rugby. This inspired schools and communities to adopt their own versions of the game, though these were often played without standardized rules.

By the 1890s, high school football started to gain structure, with leagues such as the Cook County High School League in Chicago helping to organize regional play. As the 20th century progressed, high school football expanded as more schools formed teams and joined local leagues. This era saw the introduction of standardized rules and the formation of state associations, which contributed to the sport’s growing popularity, competitiveness, and safety. These formative years laid the foundation for the widespread integration of high school football into American culture, significantly influencing both community identity and youth development.

Early history of American football outside the United States

( 1874-1932 )

From 1874 to 1932, American football began to expand its reach beyond the United States, with early games played in countries such as Canada and Cuba. The first international American football game occurred on October 23, 1874, when Harvard University faced McGill University in Montreal, Canada. This game combined elements of Harvard’s “Boston Game” rules with McGill’s rugby-style rules, marking a significant moment in the sport’s development.

American football made its debut in Cuba in 1907, highlighted by a memorable game on December 25 between Louisiana State University (LSU) and the University of Havana. This event showcased the growing international interest in American football during the early 20th century. These initial games played a crucial role in introducing American football to new regions and laid the groundwork for the sport’s global expansion in the years that followed.

ALSO READ :

- WHAT IS FOOTBALL? : THE IMPORTANT IN A GAME

- THE DIFFERENT POSITIONS : THE IMPORTANT POSITION IN A FOOTBALL GAME

- THE RHYTHM OF VICTORY : THE 7 IMPACT OF MUSIC IN FOOTBALL GAME

- THE MOVIE : A STORY OF FOOTBALL GAME